ST ANDREW THE LESS, BARNWELL, 1801-2025 by Michael Yelton

The historic parish of Barnwell was very substantial in size, but not heavily populated. The town of Cambridge, even as late as 1801, was small and closely confined around the Colleges of the University and Barnwell was then outside it.

Dr A.L. Peck, in an essay on Barnwell Priory written in 1939 to commemorate the centenary of Christ Church, Newmarket Road,[1] helpfully sets out the boundaries of the parish with reference to the features found at the time when he was writing. The northern boundary was the river, and at about the place where the railway bridge now stands it turned down and then ran along the line of modern-day Brooks Road, then struck across to the junction of Cherry Hinton and Coleridge Roads, crossed Hills Road just further out than at its junction with Cherry Hinton Road, ran along Purbeck Road and followed the line of the brook towards Lensfield Road, then up Parkside, Clarendon Road, Fair Street and Newmarket Road back to the river at Jesus Green. It will be seen that it thus encompassed the whole of what was known as the Kite area before the building of the Grafton Centre, and also East Road and the streets off it, the then wholly undeveloped Newmarket Road, Romsey Town and the town end of Hills Road.

The expansion of the built-up area was accelerated after the passage of an Enclosure Act for Barnwell in 1807. The population of the parish had varied around 300 before the Nineteenth Century, and was 252 in 1801. By 1841 it had soared to some 10000, and it was clear that further provision had to be made for the religious needs of the inhabitants. What was known as Barnwell New Church was erected in about 1828 on Mill Road, but was demolished only about 10 years later in order to permit the construction of the cemetery.

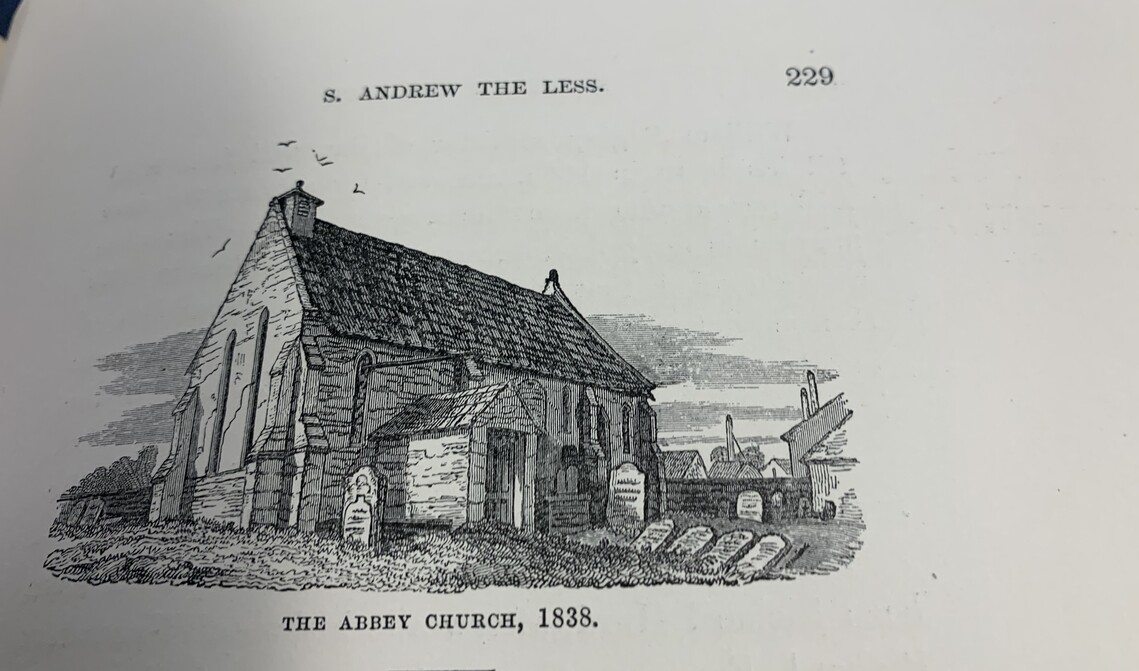

It would appear that the building of St Andrew the Less had been somewhat neglected over the years. Cooper, in his Memorials of Cambridge, published in 1866, says that the mediaeval rood screen in the church was still in place in 1826[2] but it is clear that it had been removed well before the church was restored in 1854-6. It was said at that latter time that new seating had been installed in about 1835, but otherwise it would not appear that much had been done either to the exterior or to the interior. In 1825 there were proceedings in the Court of King’s Bench by which it was sought to compel the churchwardens to repair the church, but it does not appear that much resulted from this.

There is no doubt that a revival in the life and ministry of the Church of England began in the 1830s. The Oxford Movement, which sought to restate the claim of the Anglican Church to be part of the Universal Catholic Church, is traditionally dated as commencing with John Keble’s Assize Day Sermon in 1833, but that and its later development into Anglo-Catholicism did not much affect Barnwell. Rather, it was impetus from the growing Evangelical party which provided the impetus to what happened in this area. The developments here began to occur earlier than in many other parts of the country.

In 1835 the advowson, that is the right to present to the living, was purchased by the young Revd C. Perry,[3] who had been ordained deacon in 1833 and was ordained as a priest in 1836. Perry came from a wealthy family and was strongly Evangelical in his outlook. He vested the living in trustees, so ensuring that the same theological tradition continued, as it has to this day.

It was clear that the building of St Andrew the Less was grossly inadequate for the new population and, in any event, it was still rather in the country: the area which was being built up was primarily that between East and Newmarket Roads. Perry encouraged the building of new churches to cater for the new residents.

On 27 June 1839 Christ Church, Newmarket Road, was consecrated, and its capacity was very much greater than that of St Andrew; it held up to 1400, whereas the old church accommodated only about 120. It was also built in what was a rapidly developing area. In 1842 another new church, St Paul’s, Hills Road, was opened, again in a locale which was developing fast. Perry himself moved to take charge of this and became the first vicar when a new parish was established in 1845: however, he left Cambridge in 1847 when he was appointed as the first Bishop of Melbourne. Both Christ Church and St Paul were designed by the architect Ambrose Poynter,[4] who was later also responsible for St Andrew the Great, in the centre of Cambridge.

When Christ Church was opened, the vicar of St Andrew the Less was the Revd Thomas Boodle.[5] He lived on Parkside, a more salubrious place of residence than much of the parish, and had a large family, but in 1845 he left Cambridge to become vicar of Virginia Water, Surrey, where he stayed until his death. His replacement was the Revd J.H. Titcomb,[6] another young priest, who was also a strong Evangelical, and he was in post when St Andrew the Less was restored. He stayed until 1859 and was later appointed as the first Bishop of Rangoon.

Titcomb was forceful and energetic. He had however a problem with St Andrew’s, which was becoming increasingly dilapidated, to the extent that it became unsafe to use for worship. In 1846 it was closed, and by instrument dated 26 January 1846 Christ Church was made to all intents the parish church, although the proper name of the parish remained St Andrew the Less, which has led to considerable confusion over the years.

St Andrew’s church remained disused and closed for seven years while Christ Church flourished: no more new churches were constructed at this time in the parish.

There was however an increasing impetus at this time to restore mediaeval churches, and many buildings were given radical treatment which in some cases destroyed historic details. The Victorians have in more recent times been much criticised for many such restorations, but it is easy to overlook the urgent need to repair and improve buildings which had been neglected for many years.

One of the most influential bodies promoting the design of new and restored churches was the Cambridge Camden Society, which was founded by some undergraduates in 1839. In 1841 it restored the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, better known as the Round Church, in Cambridge. It then promoted the idea that Gothic was the only proper style for Christian churches, and although its members were prohibited from involving themselves in theological disputes, it in fact became part of the tide towards Catholic worship which was being promoted by Newman’s successors. Its members were very critical of the design of the two new churches constructed in Barnwell, especially of St Paul’s. There were some who regarded the Society as too rigid and partisan in its ideas and in 1845 there were serious internal ructions, which ended with the organisation moving its centre of operations from Cambridge to London and adopting the name Ecclesiological Society.

The Cambridge Architectural Society was founded in 1846 to provide for those in the town and university who disagreed with the direction in which the Camden Society was moving. Its expressed objectives were to promote the study of ecclesiastical architecture, arrangement and decoration. Its members were nearly all senior members of the University, and the President was the Revd Dr W.H. Mill,[7] a considerable Orientalist who was appointed as the Regius Professor of Hebrew in 1848. After his death, on Christmas Day 1853, he was succeeded as President by the Revd G.E. Corrie,[8] the Master of Jesus College. Neither of these were supporters of the emerging Anglo-Catholic Movement and indeed Corrie was notorious for his extremely conservative outlook in all spheres.

Although most of the members of the Cambridge Architectural Society were Fellows of the Colleges, one who was not, but who had a decisive influence on many church matters in Barnwell, was R. Reynolds Rowe,[9] who was both an architect and a civil engineer, and in addition was Town Surveyor of Cambridge from 1850 to 1869. He is best known for designing the Corn Exchange and he was also much involved in civic affairs, as was his father, R. Rowe,[10] who was employed in the University Library. Rowe senior lived off Maids’ Causeway and in due course became a member of the congregation of Christ Church and then churchwarden of St Andrew the Less, a post later held by his son.

The Cambridge Architectural Society was much less forthright and more academic than its predecessor and initially it concentrated on listening to learned papers, often on churches and cathedrals overseas. It was however decided in the summer of 1853 to raise funds for the restoration and reopening of St Andrew the Less, and a committee was formed for that purpose.

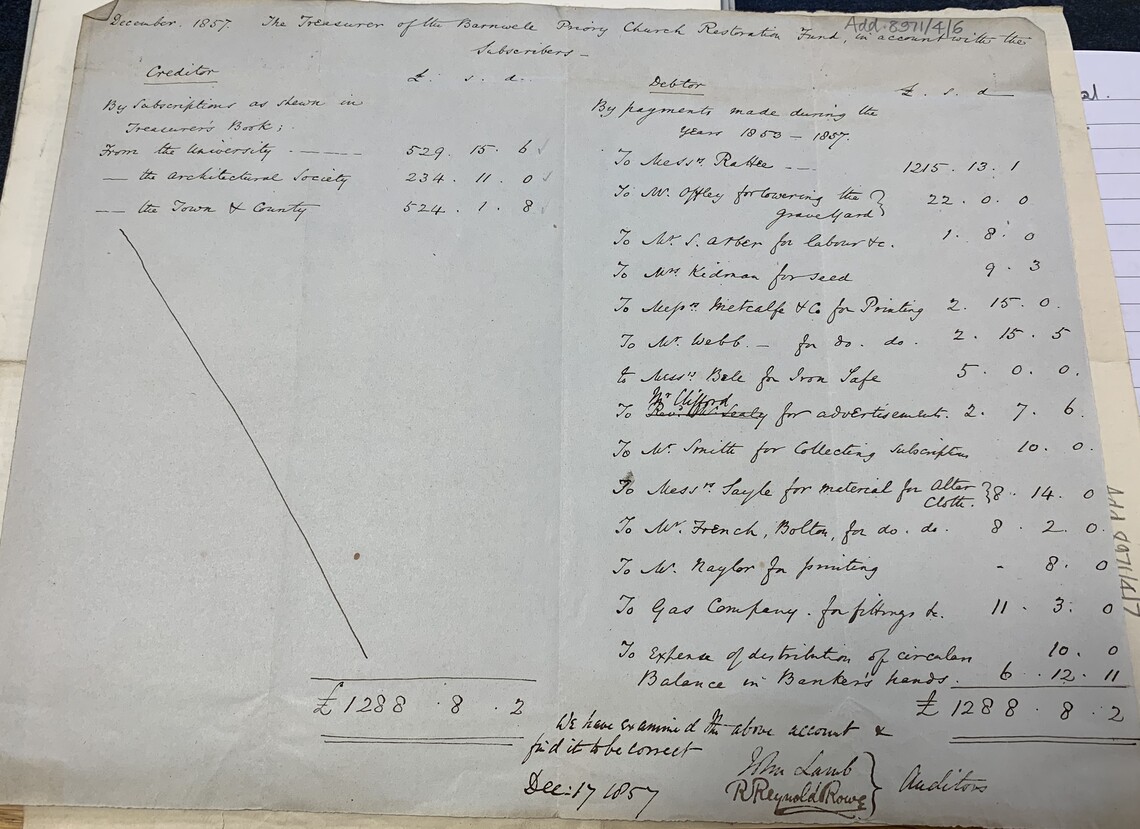

The Revd H.M. Ingram,[11] who became Chaplain of Trinity College in 1853, became an active member of the Society, and he was appointed as treasurer of the Barnwell fund. Subscribers were noted under three categories, namely University, Architecture, and Parishioners: the sums given by individuals were generally small and careful accounts were kept. Eventually about £1200 was raised, which enabled the work to be done.

The society was assisted by the fact that Reynolds Rowe was available to supervise the restoration. It was agreed that it should be carried out by Rattee & Kett, a local firm founded in 1843 by James Rattee,[12] who was then joined in 1848 by George Kett.[13] The business later carried out a great deal of ecclesiastical work, including the construction of the very large Roman Catholic church of Our Lady and the English Martyrs in Hills Road, in the 1890s.

Unlike many restorations of the time, that of St Andrew the Less was centred on repairing and making usable the building which was in existence, rather than transforming it. The enterprise was thus conservative rather than revolutionary in ethos. Work began on 7 December 1853, after a report (apparently not preserved) had been compiled on what was required. Shortly before that, on 26 October 1853, J.H. Cooper[14] of Trinity College read a paper to the Society on the history of the church and of Barnwell Priory, and this no doubt excited further interest in the project.

On 29 October 1853 the Committee wrote to H.R. Evans,[15] the Clerk to the Peace in Ely who was also Registrar of the Diocese, who, rather surprisingly to modern eyes, took the view that no faculty was required for the works proposed. Titcomb was not on the committee of the Society, but his curate, the Revd S.B. Sealy,[16] who was also his brother-in-law, was, and took an active part in its deliberations. In accordance with his views, Titcomb was very anxious that none of the new internal furnishings could be considered as favouring the still nascent Oxford Movement, and at one time he asked to be given a veto on the introduction of new articles; he was particularly exercised by the suggestion of a separate lectern being erected.

Titcomb indeed went to see the Bishop of Ely, Thomas Turton,[17] who approved the plans but wanted the prayer desk not to be on the stall but rather a few inches westward of the screen and parallel to or opposite the pulpit.

The project was begun by digging out soil around the building in order to lower the churchyard by about two feet and to repair the foundations and strengthen them with concrete; the wall on to Newmarket Road was taken down and replaced by a fence. Shortly afterwards, on 26 June 1855, an Order in Council provided that there should be no more burials in this and in a number of other Cambridge churchyards.

The building work then began, and it was decided to start with the north wall, which was in a ruinous state. It was in effect demolished and then rebuilt and a vestry with stairs to an organ loft was added on the outside of it. The roof, which was also in a precarious state, was completely replaced. It appears from the surviving archived papers that this first stage had been completed by the end of 1854; it was then decided that Dr Mill, who had of course died shortly after the work commenced, should be commemorated by stained glass being placed in the triple east window.

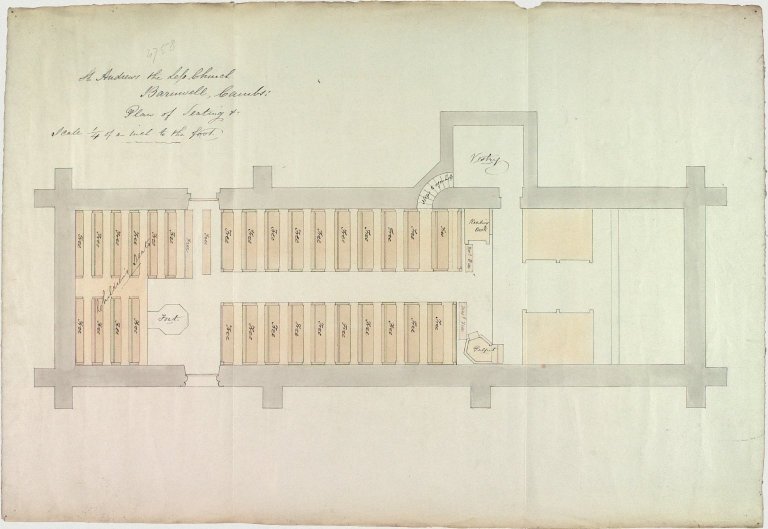

The Incorporated Church Building Society (then under an earlier name) was approached and gave a grant of £130 towards the work, and has preserved a plan showing the seating which was to be installed. Their donation and further subscriptions received enabled attention to be turned to the south wall, which was less dilapidated than the north. It dated largely from the Fourteenth Century, whereas the rest of the fabric was from the Thirteenth.

There was a porch on that side, which at one time the Committee of the Society wanted to retain, but it was demolished and the bricks from it were used in underpinning some of the building. As a temporary measure, a wooden porch was erected in its lieu. The doorway itself was restored and new doors provided there and elsewhere.

The south, east and west walls were repaired rather than replaced and a red brick facing under the west windows was removed. All the windows were reglazed, with plain glass. There had been a small bell turret at the west end: this was removed and the bells were hung at the east end. Crosses were erected externally at each end of the roof.

Internally, all the walls were replastered. Deal flooring was laid and the roof was also internally covered with wood. Minton tiles were erected in the chancel, 30 benches were erected in the nave for the congregation, and a further six in the nave. A pulpit and reading desk were introduced and a new wooden altar table set up with rails: this replaced the former arrangement in which a preaching box took up much of the east end. The font was provided with a new plinth. The only items which might be considered controversial at that time were a curtain, which was hung at the east end, and an altar cloth, which was specially embroidered.

A new organ was designed (and it appears paid for) by the Revd J. Gibson,[18] one of the Vice-Presidents of the Society and a member of the Committee, who was one of those much concerned with the project.

The church was reopened in May 1856. The renovation was comprehensive, but clearly very badly needed, and left the church in a sound state of repair.

It is clear that at the time when the church was reopened, nothing had been done in relation to the stained glass to commemorate Dr Mill. Contributions were sought to provide this. It was not in fact until 1868/9 that the three lancet windows in the east wall were given stained glass depicting the crucifixion, designed by local firm Constables, but not clear whether they were in memory of Mill.

Once St Andrew had reopened, services continued there on a regular basis, although because of its position and its capacity, it was subordinated to Christ Church.

Church extension continued to take place in the area. The new church of St Matthew, in what became known as Sturton Town after the name of its developer, was built in 1866 and was designed by Rowe. It had its own parish after 1870. In 1869 work began on the church of St Barnabas, Mill Road, which was given its own parish when it was completed, in 1888.

In 1867 the Cambridge Architectural Society restored the so-called Leper Chapel, more properly named St Mary Magdalene, in Newmarket Road, which was within the parish, but that was only used sporadically for services as there was at that time little housing that far out.

In 1873 a new church of St John was opened in Wellington Street, near the junction of Newmarket and East Roads, and was used by Christ Church as a mission church with a particular appeal to children.

This new development may seem to have adversely affected the prospects of St Andrew the Less, but in 1886 Joseph Sturton[19] purchased the site of the priory, behind the church, and developed it as the Abbey Estate, increasing the population around very substantially. It was even proposed at this time that the church should be extended, but that was another idea which did not progress. However, the new suburb meant that the church was no longer as it were isolated from housing.

In the meantime, yet further churches were being constructed in the historic parish. in 1882/3 Rowe suggested building, at his own expense, a new church, to be known as St John of Jerusalem, on the corner of Parker’s Piece, but this idea did not proceed. In 1889 work began on St Philip, Romsey Town, which became a separate parish in 1903. Thus, the very extensive old parish was substantially diminished in size as the Nineteenth Century proceeded.

The system arose of dividing the work of the parish between the vicar and his curates so that each was allocated a specific sphere. In this way, one of the curates was allocated to the Abbey Church and on occasion was transferred there from Christ Church or St John’s or vice versa. Curates normally only stayed in post for about two years, although some stayed for three or four: there were none who remained for a long period and that must have hindered the progress of the work. As with most churches at this time, a Sunday School was held and for this purpose school buildings in River Lane were used.

The most unexpected of the names of the staff of the three churches is that of the Revd H.W.G. Kenrick,[20] who was at Christ Church and St John’s in 1891-2. The tradition of the churches remained resolutely Evangelical. Kenrick was a considerable amateur botanist, and was vicar of Holy Trinity, Hoxton, in East London from 1905 to 1932. He was certainly by that time an Anglican Papalist, and was the compiler of The English Missal, which was used in the more advanced Anglo-Catholic churches; he was also an early advocate of pilgrimages to the shrine of Our Lady at Walsingham. It is not clear whether these views developed after he left Cambridge, or whether he suppressed his true position for a time.

It would appear that St Andrew had something of a renaissance between the wars. In 1924-5 a further renovation was carried out, this time by H.C. Hughes,[21] who was a member of the Architecture Department of the University and who combined some of the first Modernist work in Cambridge with a strong interest in conserving mediaeval buildings.

The work carried out at that time was far less comprehensive than the restoration of 1853-6. No plans are with the faculty papers, but the work is set out: the roof was retiled, the walls were distempered, part of the roof was decorated (which is presumably when the section over the chancel was coloured), a screen was placed over the historic piscina opening, two reading desks were installed for the choir in place of the existing desks and of one pew, a cupboard was installed in the vestry and some damaged external stonework was repaired. The most controversial addition was a new holy table, which was given under the will of a parishioner, Mrs. M.L. Pryor,[22] but of which Hughes did not approve. The vicar, the Revd Canon E.J. Church,[23] had also been given a cross for the holy table but, true to his Evangelical principles, refused to accept it. Despite the architect’s misgivings, the table was introduced and it replaced that erected after the Nineteenth Century restoration.

In 1929 a new south porch was added to the church to replace the wooden porch which had been erected in 1854-6. This project was advanced strongly by the Revd W. Hopkins,[24] who was the curate allocated to St Andrew the Less from 1927 to 1930. The porch was dedicated by the Bishop of Ely on Ascension Day, 1929. It was designed by Theodore Fyfe,[25] who was also employed by the Department of Architecture and is best known for his work in reconstructing Knossos in Crete when it was excavated, but had worked extensively at Chester Cathedral and when in Cambridge he carried out work at St Andrew the Great and in the design of a memorial chapel at St Clement to commemorate the long-serving former vicar, the Revd E.G. de S. Wood.[26]

The most striking feature of the porch is the statue of St Andrew with saltire above the door, which is rather at odds with the lack of ornamentation elsewhere in the church.

The system of allocating specific areas to the curates lasted until 1935, when the then vicar, the Revd James Thompson,[27] decided to attempt to abandon it in an attempt to unify the parish.

In 1937 a hall known as St Radegund’s was opened on Coldham’s Lane, at the far extremity of the parish; this was later replaced by a permanent church of St Stephen (now demolished), which was then attached to another church rather than to Christ Church.

In 1940 St Andrew was closed for a time and made ready to receive the congregation of Holy Trinity, in the City Centre, which had suffered bomb damage.

In the years between 1945 and about 1960 the Church of England nationally enjoyed something of a renaissance in numbers and influence. This is demonstrated here by schemes to improve the furnishings of the church.

In the immediate post-war period, the very distinguished architect Professor A.E. Richardson[28] was consulted and he suggested a series of measures to beautify the church. Only two parts of this scheme were carried out. In 1947 the font (which was near the south door) was moved and there was some rearrangement of the seating near it. In 1949 the holy table was extended by some 2 feet 6 inches and new communion rails erected, with a step up to the altar. The lectern was placed on a new base. The frontal of the extended altar had an IHS monogram on it. Rattee & Kett were again engaged to effect these alterations, which were perhaps as “ecclesiological” as any carried out at St Andrew.

Also in 1947, a new heating stove was introduced; it lasted until 1969, by which time it was noted as “obsolete” and was replaced by seven overhead electric heaters.

In 1953 a small oak tablet was erected in the chancel in memory of Agnes North,[29] who had died shortly before. This led to some fractious correspondence between the vicar, the Revd R.P. Neill[30] and the long-serving Chancellor, K.M. Macmorran,[31] who was not his own severest critic. Neill said he did not like tablets in any event but felt bound to accept the gift: Macmorran said he did not like tablets erected in the chancel if they commemorated non-clergy. This fracas over a simple attempt to remember a long serving member of the choir ended with the faculty being granted.

In 1954 a new choir vestry was erected on the north wall, on the outside of the existing north west door of the church. The building material came mostly from Corpus Christi College, which had surplus available after some works. A gabled extension was erected with (perhaps surprisingly) metal windows.

1n 1961 the north and west walls of the cemetery were repaired. It is not clear when the wall between the churchyard and Newmarket Road replaced the fence which had been erected during the Nineteenth Century restoration.

In 1970 the church was rewired.

However, it is clear that thereafter less use was made of the building. It was used for a time by a Polish congregation, and it was proposed that it be taken over by Romanians, but at present it is empty.

[1] Arthur L. Peck and Sterndale Burrows: The Church in Barnwell (Heffers, 1939). Arthur Leslie Peck (1902-74) was a devotee of Anglo-Catholicism and of Morris Dancing, who acted as subdeacon at St Mary the Less but had been baptised in the parish of St Andrew the Less; Sterndale Burrows (1875-1960) was a solicitor who, as his father had been, was a churchwarden of Christ Church. He was the Clerk of the Peace for Cambridge.

[2] C.L. Cooper: Memorials of Cambridge, Volume III, (William Metcalfe, Cambridge, 1866).

[3] Charles Perry (1807-91).

[4] Ambrose Poynter (1796-1886).

[5] Thomas Boodle (1804-83).

[6] Jonathan Hall Titcomb (1819-87).

[7] William Hodge Mill (1792-1853).

[8] George Elwes Corrie (1793-1885).

[9] Richard Reynolds Rowe (1824-99).

[10] Richard Rowe (1799-1878).

[11] Henry Manning Ingram (1824-1911).

[12] James Robert Rattee (1820-55). He had first come to prominence as a woodcarver and was taken up for that skill by the Camden Society.

[13] George Kett (1809-72).

[14] James Hughes Cooper (1831-1909).

[15] Hugh Robert Evans (1805-71).

[16] Sparks Bellett Sealy (1825-94): he had married Titcomb’s sister.

[17] Thomas Turton (1780-1864).

[18] John Gibson (1815-92); he was instrumental in the restoration of Jesus College chapel and was a Fellow there.

[19] Joseph Sturton (1815-1910).

[20] Henry William Gordon Kenrick (1862-1943).

[21] Henry Castree Hughes (known as Hugh) (1893-1976).

[22] Mary Louisa Pryor (1860-1916).

[23] Edward Joseph Church (1863-1945).

[24] William Hopkins (1888-1968).

[25] David Theodore Fyfe (1875-1945). See P.H.M. Soar: Theodore Fyfe, Architect (author 2009).

[26] Edmund Gough de Salis Wood (1841-1932).

[27] James Thompson (1891-1947).

[28] Alfred Edward Richardson (1880-1964).

[29] Agnes Maria Elizabeth North (1877-1952)

[30] Robert Purdon Neill (1910-85)

[31] Kenneth Mead Macmorran (1883-1973)